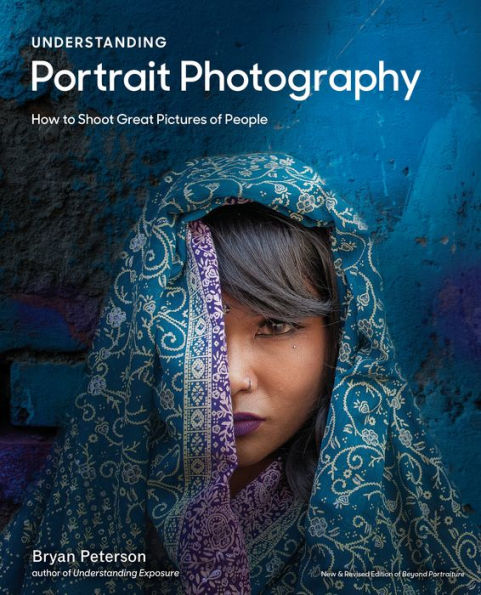

Understanding Portrait Photography: How to Shoot Great Pictures of People Anywhere

$30.00 – $65.00

Description

Author: Bryan Peterson

Capture the perfect portrait–even if it’s with a selfie–in this updated edition of a trusted classic, now with all-new photography.

Great portraits go beyond a mere record of a face. They reveal one of the millions of intimate human moments that make up a life. In Understanding Portrait Photography, renowned photographer Bryan Peterson shows how to spot those “aha!” moments and capture them forever. Rather than relying on pure luck and chance to catch those moments, Peterson’s approach explains what makes a photo memorable, how to spot the universal themes that everyone can identify with, and how to use lighting, setting, and exposure to reveal the wonder and joy of everyday moments.

This updated edition includes new sections on capturing the perfect selfie, how to photograph in foreign territory while being sensitive to cultures and customs, how to master portraiture on an iPhone, and the role of Photoshop in portraiture. Now with brand-new photography, Understanding Portrait Photography makes it easy to create indelible memories with light and shadow.

Product Details

| ISBN-13: | 9780770433130 |

|---|---|

| PUBLISHER: | Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale |

| PUBLICATION DATE: | 08/04/2020 |

| PAGES: | 192 |

| FORMAT: | Paperback Book |

| PRODUCT DIMENSIONS: | 8.51(w) x 10.49(h) x 0.50(d) |

About the Author

Read an Excerpt

Introduction

In the background, in another room, I can hear a familiar television commercial. My daughter Sophie is watching “old” television commercials on YouTube and just as I sit down to write this introduction to yet another book on photography—a book about photographing people, a subject I’ve grown to love more than any other—I hear the classic commercial for Timex watches and their tagline, “It takes a licking and keeps on ticking.” No doubt this tagline also describes me and my continued passion for image-making. Yes, my passion has taken a licking, but it’s still here and it does keep on ticking!

My first book on photographing people, People in Focus, was a scary proposition for me—not “scary” in the sense that I was afraid to photograph people (although there was some of that), but in the sense that I was being asked to write an entire book about a single subject, and I, of course, felt that photography could not and should not be limited to a single subject, especially people. Was there really that much to say, that much to show, that much to share, that much to shoot on the subject of people?

Needless to say, my own maturation process has changed this way of thinking. Now when I’m asked whether I’ll ever run out of ideas or subjects, I always respond with the same emphatic “Not in this life!” In fact, despite being told by my publisher, repeatedly, that I have more than enough material for this new book (along with nine more books on the subject), I still wish I had more time to gather additional examples of why people are such an inexhaustible photographic subject.

Obviously, you, too, share my interest in photographing people—otherwise, why are you holding this book in your hand? Whether your interest is in photographing family, friends, yourself, strangers, young or old subjects, people at play, people at work, people under strife, people celebrating, people in foreign lands, or people in your own neighborhood, I get it! Pictures of people tug at our hearts; they are, in many ways, pictures of ourselves. A photograph of a sad and teary-eyed six-year-old with a melting ice cream cone at her feet will touch most of us. We can feel her pain. Similarly, an image of three elderly people sitting on a front porch laughing hysterically may generate a number of interpretations, but one thing is certain: everyone can understand and appreciate the meaning of laughter. In addition, most of us have someone to thank—a mother, father, relative, or friend who had a camera in hand—for forever preserving small yet revealing vignettes of our personal histories.

Without realizing it, we are adding to one another’s histories with each press of the shutter. Even if you have been photographing family and friends for only a few years, those memories are capable of triggering a host of emotions that will only get deeper as the years go by. Many people are reminded of their youth as they look back on images of yesterday; that a photo reminds people of an “easier” time is the most often-heard response from viewers. Your children, just as you were with your parents, are amused by pictures of you with your old-fashioned hairstyle and “vintage” outfit, or your shoulder-length hair and beard, in sharp contrast to that shiny dome the grandkids love to rub. You tell your children that “you had to be there” when explaining your appearance back then and are quick to remind them that they, too, will look back with nostalgia and perhaps even embarrassment at the pictures you took of them just last week. “Whatever possessed me to wear baggy jeans around my knees and have orange hair?” your son or daughter might say.

At other times, photographs of people taken last year—or even today— give pause for reflection. You sigh and wonder where the time goes as you look at ten-year-old photographs of yourself and those you love. You are moved to tears and laughter as you stare at photos of your toddler daughter, who’s now eighteen and about to leave for college halfway across the country.

How you photograph your loved ones, friends, and even strangers can reveal something about you. Surprised to learn this? I’m not a psychiatrist, but I’ve done enough reading—and, more important, student critiques—over the past forty years to conclude that how we compose photographs of friends and strangers reveals some of our inner selves. Do your favorite pictures show people in a vast landscape, causing them to appear small and diminished? Perhaps compositions of this type reflect your own feelings of being overwhelmed at times, or of just how lonely life can be, or even, still, of how “small” you feel. On the other hand, do you find that you most often fill the frame with just the face of your subjects? Such compositions might reflect the great compassion you feel toward people, as well as your ability to feel free enough to interact with most anyone. The reasons why you do what you do are numerous, and in part, they define who you are; but photography—unlike any other medium—can say volumes about you (by how you shoot your subjects) in a single stroke.

My photography career didn’t begin with people as my main interest. Waterfalls and forests, flowers and bees, lighthouses and barns, and sunrises and sunsets drew 99 percent of my attention. This continued for more than ten years until one day I found myself composing yet another snowcapped peak reflected in a still foreground lake. That day proved to be a turning point as I began to reflect on the absence of people not only in my private life but equally so in my pictures. Spending countless days and weeks in nature was making me lonely.

For the next five years, I found myself making a slow but deliberate transition: I spent less and less time shooting compositions without people. I felt a new passion as I realized that the most vast and varied photographic subject was people. I felt lucky! As the song goes, “People who need people are the luckiest people in the world.” And, I was quick to discover that my camera could be a bridge in introducing myself to people—but I still had one hurdle to overcome.

Since I’m normally an outgoing person, I was amazed to discover just how shy I really was. On more than one occasion, I resolved to abandon my interest in photographing people. After all, my landscape and close-up photography was already well received by magazine, greeting card, and calendar publishers. And, of course, there was one big distinction between nature subjects and people: mountains didn’t move, flowers didn’t stiffen up (or throw nectar in your face!), and butterflies never once asked for payment.

But try as I might, I couldn’t silence the steady voice inside me that kept pushing me to return to people as subjects. The voice would grow louder when I saw particularly striking subjects, such as a lone ice cream vendor in a city square surrounded by hundreds of pigeons, a woman dressed in red walking parallel to a blue wall with her white poodle leading the way, or a white-bearded man of eighty-plus years sitting on a park bench and chuckling as he read an Archie comic book. But even during those obviously great picture-taking opportunities, I seldom was courageous enough to raise my camera to my eye and take the picture. A wave of photographic shyness would come over me. Any thought of approaching strangers, especially, would find me panicking, overreacting, convinced that, with each closing step, anything I was going to say or do would be an unwelcome waste of their time, no matter how brief my request.

Unlike the landscapes with which I was so familiar, people can, and oftentimes do, talk back, and they do have something to say. People require interaction: I had to get involved with my subjects if I had any hope for spontaneity as well as cooperation. Otherwise, if I just simply raised the camera to my eye and took the picture, my subjects would immediately become self-conscious. It was as if I were a doctor with a huge hypodermic needle, about to administer the shot of their life.

As the weeks turned into months and I experimented more and more with my feeble attempts at photographing people, it slowly became evident what was behind this new “love” developing inside of me, this love of photographing people. Surprisingly, it had little to do with the settings in which I viewed them. It wasn’t the surroundings, the colors of their wardrobe, or the amazing light that caused my emotions to stir, but rather the person in that scene. Remove the main subject and the “sentence” would lose its impact; the person was the exclamation point! Funny how only a few months prior, I’d been cursing people for getting in my shot and now I was afraid they would leave—unless, of course, I approached them and explained their importance to the overall composition, and with any luck they agreed to stick around for “1/60 of a second.”

Bryan Peterson is a professional photographer, internationally known instructor, and founder of The Bryan Peterson School of Photography. He is also the bestselling author of Understanding Exposure, Learning to See Creatively, Understanding Digital Photography, and Bryan Peterson’s Understanding Photography Field Guide. His trademark use of color and strong, graphic composition have garnered him many photographic awards, including the Art Director Club’s Gold Award and honors from Communication Arts and Print magazines.

Bryan Peterson is a professional photographer, internationally known instructor, and founder of The Bryan Peterson School of Photography. He is also the bestselling author of Understanding Exposure, Learning to See Creatively, Understanding Digital Photography, and Bryan Peterson’s Understanding Photography Field Guide. His trademark use of color and strong, graphic composition have garnered him many photographic awards, including the Art Director Club’s Gold Award and honors from Communication Arts and Print magazines.